Markus Stegmann

Raging Surf

Observations in the Ocean of Color and Figure

. . . the dark leaf,

And it was

The growth before all else

and the Syrian

ground,

shattered, and flames right under the soles

It stabbed

And the disgust

Arrives for me from raging hunger

Friedrich with the bitten cheek

Eisenach

the glorious

Friedrich Hölderlin (1770 – 1843)1

In the middle of the day a fear

I do not know of what

Above me, the yellow sun

Before me, the Kottbusser Tor

Behind me soft calling and whispering

Every step is heavy to me

Who will do anything to me no one is here

But everyone is behind me

For it is quiet in the street

I have thought myself out

Whatever fire I will

I have kindled

Thomas Brasch (1945 – 2001)2

Character

Are they running into the crashing surf or are they passing over clouds? Is it a sporting competition or a sudden catastrophe? One thing is clear: Norbert Bisky’s figures in “Iconoclasts” (2017) are engrossed in stormy movement. Even if we cannot recognize the spatial context, and cannot evaluate the significance of the scene — whether it is positive or negative — the people are in motion, and, it appears, will remain in motion for some time. This is, in fact, at once a remarkably sparse statement and a full-blown paradox: the emotional state of those represented is indefinable, remaining in a state of fluid ambivalence, and it may at any moment plunge from one extreme into another. Any emotional impulse is a possibility, from a harmless game to the direst emergency.

Why is it that we cannot determine the condition of these people? Almost all of them are looking away from us, and only two faces can be seen; one of these faces is too cut-off to be recognizable, while the other might suggest pain, a high degree of concentration, or even grim humor. We cannot see the other faces. As in many Romantic paintings — such as “Zwei Männer in Betrachtung des Mondes” (Two Men Contemplating the Moon) (1819/20) by Caspar David Friedrich — they are turned away from the viewer, looking into the depths of the picture or of the landscape. In “Iconoclasts,” Norbert Bisky does not spare emotional energy — quite the contrary. That energy is expressed in the independent life of the colors and the flickering forms, resulting in a multiplicity of meaning rich in allusions: the melancholic spiritual condition of the protagonists in the expressive mood values of nature. They stand there, faces turn to the moon, and hope for a happier tomorrow, aware that this will likely not come to be, but they appear to be absorbed in that hope all the same.

In addition to leaving it undecided as to whether he means to show sea, clouds, or rough grass, Bisky also leaves indeterminate the state in which nature finds itself: like the figures, it appears to be in violent motion — putting us in mind of a storm — but we can barely form any other conclusions. Is it a cloth, a tent, or an uprooted tree flying in at the top left? Is this structure as light as plastic sheeting or as heavy as a tree? Do we see flames flickering here and there on the ground? Is this burning grassland? And is it debris from a detonation that is plummeting down from the sky , or lava from a volcanic eruption? The longer we look, sinking into the picture as we search for answers to very simple questions, the more the picture appears to evade our rational means of access, and the more puzzling — not to say contradictory — its potential messages become. This picture plays strange games with us: the bright colors, the movement of the figures, the embracing gesture in the picture’s middle ground are strong emotional signals that enter our blood instantly like glucose, speaking to us directly. The partially cut-off figure at the lower edge of the picture and the upper arm on the far left bridge, very naturally and yet playfully, the gap between the events in the image and ourselves: standing in front of the picture, we instantly become involved in the events within it: it thoroughly draws us into the image, into its spatial depths.

The narrow knife-edge between the game and the abyss dramatically culminates in the instant we discover that the group of three in a close embrace possess two arms too many, or one too few. It remains uncerftain whether someone is missing, and, if so, why he or she is no longer visible. A filmic movement flows within a picture, a sudden cloud, or did an arm, in desperate extremity , remain desperately holding on even as the person it belonged to vanished? “Iconoclasts” is just one example of a picture by Bisky that demonstrates a narrow and unstable knife-edge between complementary emotional levels. Disturbingly, we remain uncertain which feelings we are encountering. We stand mystified before the picture, even though we are part of what is happening. To put it another way: if one takes Bisky’s pictures as witnesses to time, it is disconcerting to see how a situation can change from one second to another. A harmless holiday mood becomes a nightmare; brutal violence breaks into the untroubled everyday suddenly, without warning. This is relevant not only to the terrorist acts that have been on the increase for years, but also to the helplessness of the individual in virtual reality , in the face of an anonymous collective. All areas of life — and, soon, all ages of life — are subject to dangerous, abrupt changes in their everyday existence. The certainties upon which one would like to call on in uncertain situations are now as eroded and vague as the ambiguous ground in “Iconoclasts,” whose composition and stability or instability we cannot determine. What endures unchanged is the vulnerability of human beings and the loss of certainties — if, indeed, they ever existed.3 The fact that Bisky, in spite of all the figuration, offers no further narrative indications — while they are plainly consciously present — is the great strength of his pictures: thus, they find themselves drifting in a somnambulist state that may at any moment become toxic. Theatrically dramatic as the image-language is, the diverging possibilities for reading the context are in equal measure sensitively differentiated. Whichever of these readings we choose, we are left with existential uncertainty, to the extent that we are no longer sure of ourselves, experiencing ourselves as multiple characters with diverging heads and hearts.

If one ultimately consults the title in an attempt to throw light on this obscurity, the content dimension is, paradoxically, expanded: iconoclasm describes the destruction of holy images, especially in Christianity, such as the Bildersturm or the destruction of images in the sixteenth century. From this perspective, the figures are to be regarded as destroyers of images, which poses the question: which images are meant? The image in which they are represented, the image as a metaphor for art, the image of themselves, or the image of their time?

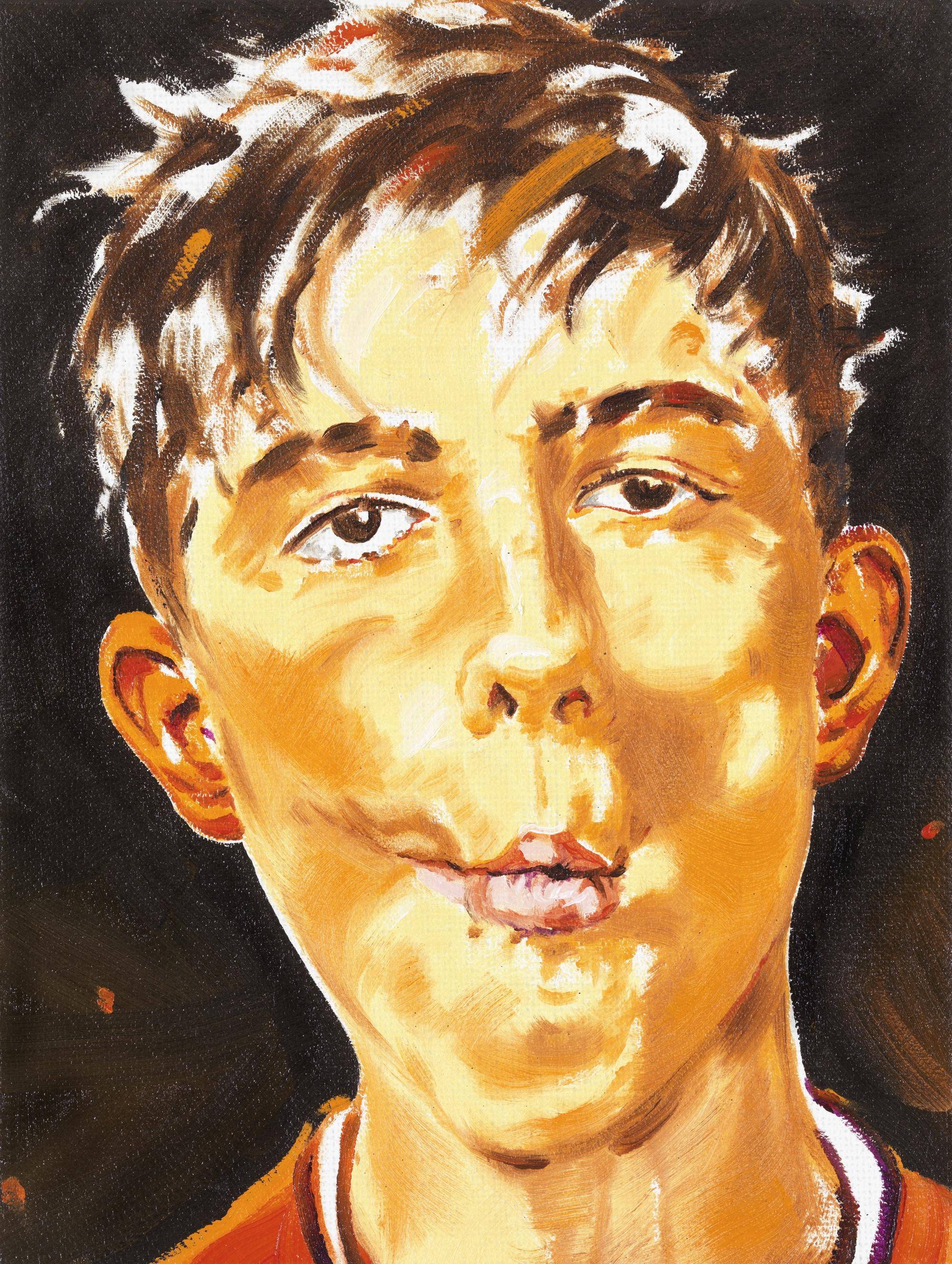

Family

Bisky dedicates his exhibition at the Museum Langmatt to the theme of family. During our discussions in the autumn of 2017, he became interested in the family history of the Browns, who, as one of the founding families of the ABB (formerly the Brown, Boveri & Cie), had the Langmatt house built as their residence between 1899 and 1901. To some extent, the history of the Brown family reminded him of his own history. In February 2018, Bisky visited Langmatt in order to view hundreds of historic family photographs in the museum archives, most of which were taken between 1880 and 1975. He then used these photos as a basis for creating new images for the exhibition, with family as the theme.

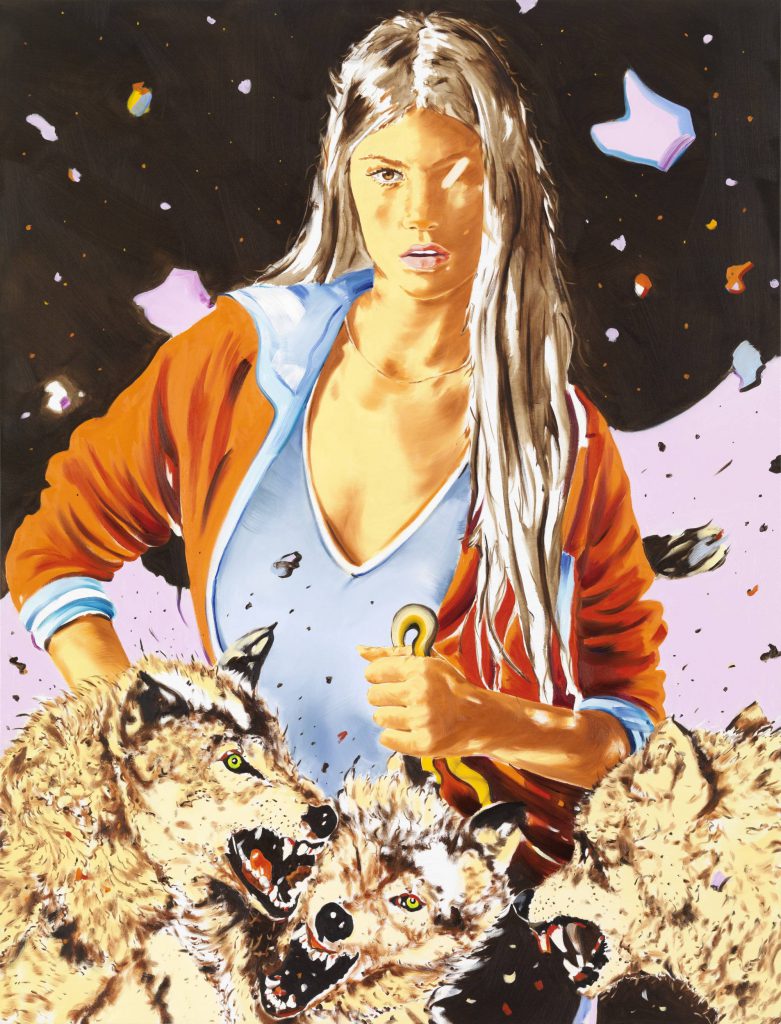

At the same time, it became evident that this theme is a thread running through his artistic work, at least since the 2008 triptych “Craving,” which is dedicated to his deceased youngest brother. In the left-hand and right-hand images, wolves are tearing apart unidentified, brightly colored objects that might be identified as clothing. The central image shows a young man, his upper body exposed — that is, with the clothing removed — who appears to have triumphed over one of the beasts. It lies twisted on its back in front of him, brought down, and, it seems, become a piece of “clothing” itself. That which, in the images on the left and right, had destroyed the seeming protection, has now itself becomes fragile “protection.” A puzzling whirl of color at the man’s head might be read as physical injury, but perhaps more probably can be read as a psychological injury. Who has triumphed over whom? Has the wolf defeated the man, or has the man defeated the wolf? The Roman poet Plautus (254 – 184 BC) once said “Victi vincimus,” or “conquered, we conquer”: two wonderful words of hope in the midst of defeat.

Can we call “Iconoclasts” a family picture? Not in the traditional sense, surely. Even if their clothing suggests that the picture represents both female and male figures, Bisky’s definition of family is far wider than this: an open group of persons whose relationships to one another is generally not described in any more detail. Three, four, five, or more people are active within his pictures. Typically, their actions and the sequence of their movements relate to the other figures. The focus is on a small group of people of the same age, rather than a family in the sense of blood relations and successive generations. The motive that binds them together as a group varies widely: the spectrum includes seemingly idyllic bathing scenes in a natural setting, sporting competitions, revolutionary uprisings, or a collective plunge from burning high-rise buildings. Individuals are not left alone with their fate. This does not save them from their existential predicament, but this is revealed to be a shared predicament. For moments, the horror of the individual is united with that of others, so that there is a hope of escaping the catastrophe at the last second through a shared forceful action.

This group engaged in shared activity recurs in Bisky’s work, although the goals and the context are rarely definable. The subjects in the paintings are typically in dynamic motion, exerting physical energy. The uni of space and time characterizes the group, and thus what can be defined as family in the widest sense. Bisky implicitly confronts the traditional family of blood relations — into which one is born without volition and which one remains a member of throughout one’s life, whether one wishes to or not — with a different model. This model rests upon being part of a group, at least temporarily — whether willingly or otherwise remains uncertain. How long the association will continue is equally uncertain. This is, in fact, also true of the traditional family — although customs and conventional behavior allows us to retain family ties for a long time, even if there has been no sense of commonality for many years. Either way, these units of community are today fragile and easily broken. There are no certainties, although traditional family models like to claim there are and like to define themselves precisely by this. Every commonality can be for a limited time only, even the smallest imaginable between two people. Paradoxically, this is happening in the Western world, of all places, which, for virtually the first time in its history, is in a state of relative peace.

Images such as “Levante” (2014), “Trunkenes Schiff” or Drunken Ship in German (2017), and “Tiroteo” (2017) are examples of groups with different connotations that could be described as emotionally united communities. The symbol of the cross shows that “Levante” (the French levant means “sunrise,” referring allegorically to the Orient) signifies a group with religious tendencies. In any case, the carrier of the cross encounters persons without religious attributes or behaviors. How the religious context is constituted — whether it is film, theater, or advertising that provides the background to these events — remains ambiguously open. In “Tiroteo” (Spanish for “shooting”),the group is interfering in what is plainly a political event. Stones are being thrown, and perhaps also Molotov cocktails — we can see that the asphalt is in flames here and there. Massive palm leaves localize the powerful confrontation somewhere in southern climes. It is not possible to be more geographically specific, making the picture a metaphor for political or social resistance.4 “Trunkenes Schiff” is dominated by a powerful confusion of bodies, large leaves, and autonomous color surfaces with no representational definition. Two of the three faces are partially cut-off or covered by a color surface, so that their expression, and thus the people’s emotional state, is excluded from our interpretation. The third person is highly concentrated, but the color once again obscures what is happening, putting interpretation of the content virtually beyond our grasp. We cannot even verify whether these people are actually on a ship — and, the longer we look, the less significant we feel that this is to the picture’s message. Wherever this may be, it is fairly violently out of balance.

In many other pictures by Bisky, people operate as random or voluntary communities with a shared fate in great extremity. Whether or not they can escape this catastrophe remains disconcertingly uncertain. At the same time, the desperate situations transform us from viewers into voyeurs, so that all we can do is experience the dramatic scenes as “onlookers,” even though we do not wish to. But to look away would be to experience being parted from the picture. “Übergepäck” (2008), “Alles wird gut” (2011), “Palindrom” (2017), and “Big Trilemma” (2017) are striking examples of the great catastrophe, the threat of the destruction of the individual and the group. Even if several persons are caught up in the tragedy, we experience the single person as being once again on their own. The motif of falling is ever present. The choreography of the body creates nagging doubts as to whether this might not be a daring performance in progress — possibly the whole thing is a cinema-worthy depiction of the competitive economy.

Form and Figure

When one looks at Bisky’s pictures in terms of their formal characteristics, what one consistently sees is a dynamic flicker. A vibration of colors permeates persons and objects by empty white spaces and expanses that overlie them, and they are cut up and fragmented by them. The energies that constitute people are contending against the energies of destruction. A figure, a leaf, an animal appears to take on form and to lose it in the same moment. Nothing achieves certain about itself. Identity is a flickering, like fata morgana. Only small fragments of the objective world can be recognized, for moments only, before they at once vanish into brightly colored nothingness, as if they felt guilt. Above all, do not be recognized and named: that appears to be the signal sent by the fragments.

The autonomous properties of the brilliant colors are strongly developed. The young bodies may appear powerfully muscular, concentrating their energies in a reciprocal embrace, but the colored surfaces are cold and emotionless, gnawing at their bodies, eating their faces away, and reliably exploding narrative connections. In that, the people have forfeited their individuality — including their age and clothing — and instead constitute a commercial marketing type; they indicate considerable empty spaces in the contemporary individual, in spite of the dynamic energy that they are capable of developing.5 Are the depicted figures stereotypical idols of a consumerism-fixated society, polished in advertisement and film? Is the great transformation that springs out of so many pictures towards us with heroic vigor now just the well-trained mechanics of material seduction?

For all the seeming non-ambiguity of their figurative nature and the seductive power of their polychromatic character, Bisky’s pictures show their incomparable strength here: they pose sensitive questions where, at first glance, everything looks simple. Where one thought one had understood everything and decoded the emotional state of the depicted people, they go deeper, emotionally speaking, into the moment. The pictures transport us by virtue of their sensory power, drawing us into their illusionistic depths of space, seducing through their somnambulistic beauty of movement and color and, of course, through their heroic gesturing of graceful bodies. The images are tantalizing butterflies, dancing bewitchingly before our eyes, and yet it seems as though they might at any time collapse in death. Bisky’s great themes are the reverting of beautiful appearances, the sudden loss of supposed certain and identity. It is as though there were a permanently lurking danger that the electricity will suddenly cut off, that there will be a blackout, that the plug will be pulled. Dream and nightmare, reality and hope diffuse into one another, blur together, and can barely be distinguished from one another. Bisky’s multiple ambivalence surprises us with deep insights into human existence, but without espousing the “existentialistic” mode and accusing the world as other gurative paintings do. The permanent vulnerability of both the individual and the group is not presented as a lament, but shows itself, as if in a brightly-lit operating theater, as inseparably linked with the human beings, so that one cannot begin to operate to remove it. The beauty of color and figure, the supreme energy and lightness of the movements; all of these help us to accept permanently looming death. Even as it plunges down, the sword of Damocles loses its horror, as if we could not die any more.

The somnambulistic, energetically intensive state of being in mo-tion with people of a shared intent is a central statement of the pictures — although they also show, time and again, how short-lived the group is, how abruptly a catastrophe drives the individuals apart. In spite of appearances, it is not so much the figures that appear heroic as these provocative moments on the knife-edge between reality and madness. In the pictures, they extend infinitely — while, in fact, they last only for the shortest of moments. The figures are assembled theatrically, positioned within the scene with perfect composition and showing their muscular bodies to best effect, but they are not heroes. It is true that they are good to look at. But personality and feelings vanish behind the beautiful appearance. To overstate somewhat: we see gestures, not individuals. These are gestures in the face of an unexplainable, fateful situation that has suddenly overtaken them.

Here, Bisky’s position is distinct from other figurative positions in contemporary art that — if not deliberately, then unconsciously — are burdened with one-dimensional socio-critical meanings due to their readily-readable representational character. It is easy for gurative art to become moralizing. There is, of course, plenty to find fault with in the world. That is beyond question. It is by no means true that Norbert Bisky avoids political and socio-critical opinions. On the contrary, his pictures are characterized by an unstable balancing act: the aspect which is fearful never arrives alone. It holds in its arms the beautiful appearance, the lightness, the randomly experienced, endured moments, in a firm embrace.

1 Friedrich Hölderlin, from “Pläne, Bruchstücke, in Jochen Schmidt, ed., Friedrich Hölderlin, Sämtliche Gedichte und Hyperion (Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig, 1999), p. 436 f.

2 Thomas Brasch, “Mitten am Tag eine Furcht,” in Der schöne 27. September, Gedichte (Frankfurt am Main, 1980), p. 32.

3 The fall of the Wall in 1989, the terrorist attacks in Mumbai 2008, which Norbert Bisky experienced at close quarters, and the death of his younger brother (which took place in the same year) are fundamental destabilising events and upheavals with far-reaching content-laden and formal consequences in Bisky’s painting.

As Jeanette Zwingenberger notes: “In fact, Bisky’s horror scenarios don’t just play with our fantasies; they are also veritably a form of working through of traumatic experiences, such as the terror attack on the Taj Mahal Palace luxury hotel in Mumbai in November 2008, which he witnessed, the early death of his younger brother, or mass panics such as events in Duisburg in 2010. Bisky’s image repertoire draws equally on personal or society-wide events and on … film scenarios and standard elements of the media world.” In Jeanette Zwingenberger, “Menschenfresser und liquide Körperwelten” (“Human Eaters and Liquid Body Worlds”), in Norbert Bisky – Zentrifuge, Dorothée Brill ed., exh. cat. Kunsthalle Rostock (Ostfildern, 2014), p. 113.

4 Norbert Bisky’s answer to the question of whether or not art ought to be political was: “A very complicated question. … Personally, however, I do not wish to paint any pictures that entirely rush by my time, and are thus, apart from their decorative value, completely irrelevant.” “Der Bilderträumer,” Norbert Bisky interviewed by Jörg Harlan Rohleder, in Focus, September 9, 2017, p. 106.

5 Norbert Bisky’s critical undermining of the Socialist Realism body ideal and of the Western advertising industry has been variously referenced: Hubertus Gassner speaks of “an art that bids farewell to state socialism” and “an amalgam of the beautiful false appearance of prescribed image worlds and the reality of direct experiences.” In Hubertus Gassner, “Norbert Bisky – Dorian Gray,” in Rostock 2014 (see note 3), p. 15.

Again, Zwingenberger: “The group compulsion is based on a feeling of affnity that results from an ideal body image, which rejects any deviation as foreign. Homosexuali is strictly forbidden. is unfailing, perfect body image, the incarnation of the authority of the stronger and the victor, was presented by the National Socialist regime in propaganda scenes, and was revisited by Socialist Realism. To this day, the manipulative visual language of our consumerist world, which markets the perfect body and an extreme body cult, draws on this tradition. Bis initially focuses on this advertising aesthetic by making use of it and quoting it. In the process, however, their perfection becomes fragile – in a perdious and brutal manner.” In Jeanette Zwingenberger, “Menschenfresser und liquide Körperwelten,” (see note 3), p. 109. And here Bühler: “His (Bisky’s) criticism of consumerism is embedded in resistance against any ideological pressing into service of body representations, whether socialist or consumer- ist.” In Kathleen Bühler, “Die Lust, das Fleisch und der Tod,” in Rostock 2014 (see note 3), p. 43 f.